MUSICAL NEWS

AT THE NCEM

Have you ever thought about how people heard the news in the 17th century? Long before the internet, TV or radio, people used music, songs and illustrations to share information. Find out all about how to make your own musical news in this resource pack for children in Key Stage 2 (aged 7 to 11).

Resources are presented in the form of guidelines and ideas to help teachers and parents lead the activities with their pupils.

Through these activities, children will:

ACTIVITY 1

- Learn about ways in which people heard the news in the 17th century.

- Learn to sing a ballad about a hailstorm in London in 1680.

- Look at an original printed ballad and discover what we can learn about the past from broadside ballad sheets.

ACTIVITY 2

- Create words for their own ballad and sing it.

- Illustrate their ballad, if possible using printing techniques similar to those used in the seventeenth century.

- Print their own broadside ballad for display.

ACTIVITY 1

THE HAIL BALLAD

This activity looks at how people heard the news in Restoration England. They look at the role of songs, known as broadside ballads, in communicating the news, focusing on a ballad from 1680 about a hailstorm in London.

1.

Begin by asking children how we keep up to date with the news. What different ways are there to find out about current events? Make a list, which will probably include the following:

• Internet

• Radio

• Television

• Newspapers and magazines

• Word of mouth

2.

Ask the children which of these ways to hear the news were available to people in Restoration England. (If the children have studied the Great Fire of London and the diaries of Samuel Pepys, you can ask them what ways Samuel Pepys would have had to hear the news.) Make a list, which should include:

• Newspapers

• Word of mouth

3.

If you have time, explain that newspapers were quite new in Samuel Pepys' time. Around the middle of the seventeenth century, the news started to be printed in pamphlets, which were printed and distributed around the country. During the English Civil War, they were used to inform people about battles and various political manoeuvres. Sometimes they were quite biased, openly supporting one particular side. These were usually one-off pamphlets, not newspapers that came out every day or every week. Regular newspapers began in the 1660s. The London Gazette is the oldest regular newspaper, which was first printed in 1665.

4.

Ask the children how the majority of people would have heard the news. Would it have been from newspapers or by word of mouth? Why? If they have not already said so, explain that the most common way to hear the news was by word of mouth. This is because not everybody could read, and because newspapers could be quite expensive.

5.

Ask the children what problems there might be with people spreading the news by telling it to each other. They will probably say that the news might not be accurately reported, or that people might exaggerate the stories. Could this be the beginning of fake news!

This is one reason why there were official people to communicate the news orally. Many towns had a 'town crier', whose job was to shout out the news.

The town crier would stand in a public place, like a market square, wear a brightly coloured coat and carry a bell, which he would ring to attract people's attention. He would shout 'Oyez! oyez! oyez!', which is a corrupted version of the old French for 'listen!' The town crier would then read the news in a loud voice.

Afterwards, he would pin a sheet containing the news on the door of a tavern, so that people could read it.

You could show them a picture of a town crier. Town criers had royal protection, and attacking a town crier carried a heavy penalty. Ask children why this was the case. They will probably say because the town crier might bring bad news. One example could be an increase in taxes.

6.

Explain that town criers were not the only people that communicated the news orally. Often, people would make up songs to tell the news.

They composed rhyming verses and sang them to well-known tunes, in taverns, at markets and fairs, or in people's homes. These songs are known as ballads. Sometimes ballad singers would stand on street corners and sing the news, as in this picture. Often, travelling tradesmen, or pedlars, would sing ballads in the different places they visited.

7.

On 18th May 1680, a violent hailstorm hit London. We know this because a ballad was written about it. The ballad's tune and a selection of the original sixteen verses can be found here (this is an external site). After a vocal warm-up, teach the song and sing it together.

LISTENING ACTIVITIES

Hail Ballad

Backing Track

Hail Ballad Music

Hail Ballad Words

8.

Those interested in learning more about the history of broadside ballads may enjoy this site put together by The Carnival Band with monies from ARHC

9.

Ask the children why people might have made up rhyming verses and sang the news? Discuss the fact that it is often easier to remember rhymes than prose, and that the sound of singing can often be heard above the hubbub of a busy market place, so that pedlars would have been able to attract people's attention by singing.

10.

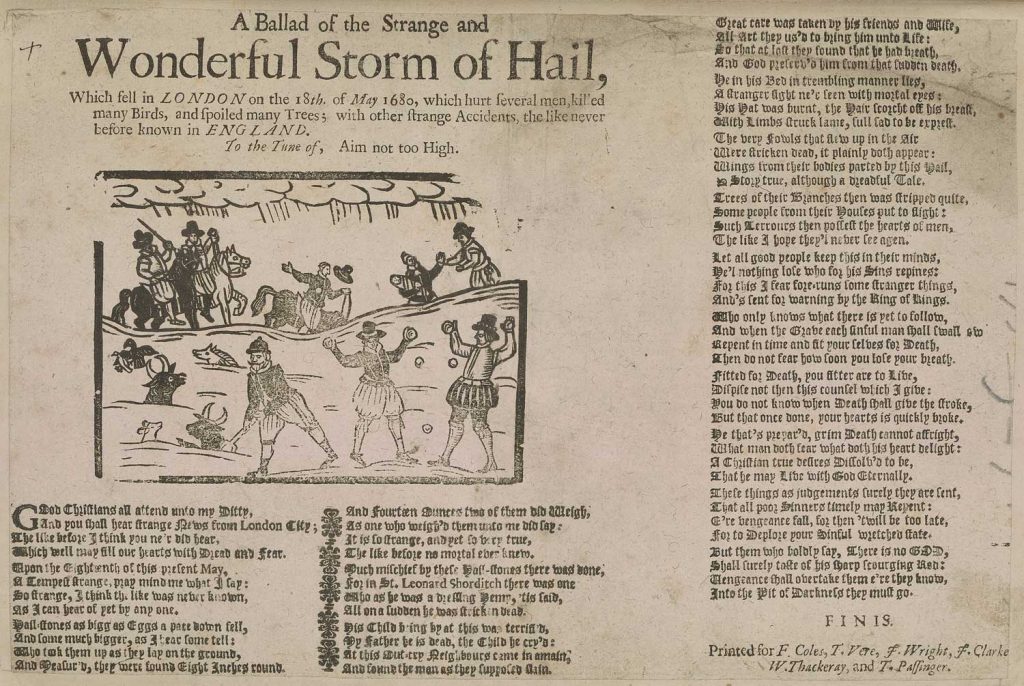

Look at the image of the hail ballad. Ask the children the following questions:

• How do we know what the ballad is about?

• Can you see any printed music?

• How did people know what tune to sing?

• Look at a verse of the ballad. What makes it difficult to read?

11.

Ask the children whether they think that the story told by this ballad is a 'true' account of the storm. Discuss whether the story might have been changed or exaggerated by the ballad writers. You may like to compare the ballad with ways the news is reported today. Can we always believe what we read in the newspapers?

12.

Explain that not all broadside ballads told the news. Some recounted historical events, but many told made-up stories. Robin Hood was a favourite character in broadside ballads. Some ballads are songs about friendship and good company (such as the famous ballad, 'To Drive the Cold Winter Away') but most tell stories: of knights, kings, lovers or common folk. Many are rather bawdy!

13.

Explain to the children that thousands of broadside ballads were printed between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some people made collections of ballads, one such person was Samuel Pepys. He collected over 1,800 ballads, and filed them under different categories. The ballad about London's hailstorm is included in Pepys' collection

ACTIVITY 2

Using the information learned in Activity 1, children have the chance to compose their own broadside ballad, as well as illustrate it, print it and perform it.

Write your own broadside ballad

1.

Look at verse two of the hail ballad:

Upon the eighteenth of this present May,

A tempest strange, pray mind me what I say.

So strange, I think the like was never known,

As I can hear of yet by anyone.

First, count the syllables in each line. You should find that each line has ten syllables.

Now look at which lines rhyme. You should find that the rhyme scheme is a a b b (lines one and two rhyme and lines three and four rhyme).

2.

Choose a topic that you would like to turn into a ballad. It could be something in the national news, or something that happened at home or in school. Have a go at writing the story in rhyming verses, making sure that you have ten syllables in each line. Here is an example to help you:

On Monday afternoon at two o'clock,

After PE, poor James had lost his sock.

Later he saw it hanging from the light,

To fetch it down he stretched with all his might.

Stretch though he did, he simply could not reach.

All of his classmates joked and jeered and screeched.

James placed a chair upon the teacher's desk,

And climbed upon it, while we held our breath.

James grabbed the sock and everybody cheered.

Just at that moment, Mr Jakes appeared.

James has detention, what a dreadful shock,

All for the sake of one lost, lousy sock!

3.

Once you have composed one or two verses, have a go at singing your ballad; use the backing track if you need to.

Illustrate your ballad

Children could draw a picture to illustrate the ballad's story. To make it look like pictures on seventeenth-century broadside ballads, you should keep the illustration to black and white. If you want to be even more 'authentic', you could make this into a printmaking project. Lino printing is a good substitute for woodblock printing (this involves sharp tools, so should not be attempted with very young children), or you can use polystyrene sheets, cutting into them with a ballpoint pen.

Create your own broadside ballad sheet

Once you have written your ballad, type it on a computer, using a gothic font like 'Old English'. Think of a good title for your ballad, using the hail ballad as an example. You can either scan your illustration and then print a ballad sheet complete with title, illustration and verses, or print the title and verses, cut them out, together with the illustration, and stick all the separate elements of your ballad sheet onto another piece of paper.

With thanks to Education Consultant Dr Cathryn Dew who developed these resources for the NCEM’s Learning and Participation programme.

Education Resource

MUSICAL NEWS